On the geopolitics of “platforms”

Robyn Caplan is one of ten 2015 Milton Wolf Emerging Scholar Fellows, an accomplished group of doctoral and advanced MA candidates selected to attend the 2015 Milton Wolf Seminar. Their posts highlight critical themes and on-going debates raised during the 2015 Seminar. In this blog post, the evolving relationships between social and traditional media and between politics and information policy regimes are reviewed.

In the last year, questions about the roles that both non-traditional and traditional media play in the filtering of geopolitical events and policy have begun to increase. Though traditional sources such as The New York Times retain their influence, social media platforms and other online information sources are becoming the main channels through which news and information is produced and circulated. Sites like Facebook, Twitter, Weibo, and other micro-blogging services bring the news directly to the people. According to a study by Parse.ly, the era of searching for information is ending—fewer referrals to news sites are coming from Google, with the difference in traffic made up by social media networks (McGee, 2014; Napoli, 2014).

In the last year, questions about the roles that both non-traditional and traditional media play in the filtering of geopolitical events and policy have begun to increase. Though traditional sources such as The New York Times retain their influence, social media platforms and other online information sources are becoming the main channels through which news and information is produced and circulated. Sites like Facebook, Twitter, Weibo, and other micro-blogging services bring the news directly to the people. According to a study by Parse.ly, the era of searching for information is ending—fewer referrals to news sites are coming from Google, with the difference in traffic made up by social media networks (McGee, 2014; Napoli, 2014).

It isn’t just news organizations that are finding greater success online. Heads of state—most famously President Obama—have used social networks to reach a younger generation that has moved away from traditional media. This shift, which began as a gradual adoption by state and public officials over the last several years, is quickly gaining speed. Iranian politicians, such as President Rouhani, have also taken to Twitter, a medium still banned in their own country. The low barriers to entry and high potential return make social media an ideal space for geopolitical actors to experiment with their communications strategies. ISIS, for example, has developed a skillful social media strategy over the last few years, building up a large following (which emerged out of both shock and awe) with whom they can now communicate directly (Morgan, 2015, p. 2). As more information is disseminated through these platforms, considering the role that technological and algorithmic design has on geopolitics is increasingly important.

Over the last several years, we have seen a rise in the use of social media and other new technologies by geopolitical actors, as well as the implementation of new communication and information policy regimes to address the potential uses of these technologies. Through a series of case studies of the global events that occurred during 2014, panelists and attendees at the 2015 Milton Wolf Seminar sought to understand how geopolitical actors were situated and being situated by this new communication regime. Seminar discussions explored the ways that old communication strategies were being imported to new technologies and how new strategies were emerging out of the technical affordances of new platforms.

The 2015 Milton Wolf theme, “Triumphs and Tragedies: Media and Global Events in 2014,” highlights both the consequences of a tumultuous year of old and new conflicts as well as the dichotomous and often paradoxical uses of communication and information technologies to advance and shape domestic and foreign policy. The geopolitical events that defined the last year, such as the annexation of Crimea and the emergence of ISIS onto a global stage, left their marks in the form of newly drawn territories and in the digital trails left by the spread of information online.

In truth, the theme of the conference underscored sentiments of ambivalence about the internet’s former promise. Despite lingering optimism about the potential of the internet and social media to level hierarchies and enable citizen mobilization, it is apparent that this new communication regime is no less susceptible to control and manipulation than previous global media systems. As the seminar progressed, case studies of how state and non-state actors were making use of these systems graduated into discussions of media governance frameworks and the complex relationships emerging between technology companies, government, and a global public.

The New Technologies of Geopolitics

Information technologies and social media networks are the sites for new contestations of power—battles that are happening in real-time and for the world to see. Information flows from the powerful to the public are harder to predict and model than in the past (Bossewitch & Sinnreich, 2012, p. 2). In response, states and corporations have expanded their efforts at surveillance and information control, as well as their attempts to increase transparency and engage citizens directly online. As states begin to adapt to contemporary communication practices, understanding the social, political, technical, and economic responsibilities of stakeholders operating in these networks is becoming increasingly important to the development of new media governance frameworks.

Throughout the seminar, participants discussed the use of social media in the production and circulation of strategic narratives, otherwise known as rationales put forward by states to strategically advance policy aims. Though these rationales often grow out of competition—supporters versus opponents—these strains are now more difficult to predict and control (Price, 2015). News that is transmitted by a wire, like AP or Reuters, is sent through an echo chamber of blogs, status updates, and retweets. Because of the increased speed at which media can be produced and distributed, state and non-state actors are using new strategies to both control their own messages and those produced by others.

From a more positive stance, governments and public officials are using online tools as a way of sharing news and information directly with citizens. Local governments have found online media to be especially useful for communicating information to residents in crisis situations (Graham, Avery, & Park, 2015). For instance, with widespread power outages during Hurricane Sandy, most New Yorkers got their information by following government agencies and officials on Twitter (Rea, 2013). Public officials are also using the medium to announce breaking news. Recently in the U.S., Hilary Clinton took to her Twitter account to announce her candidacy for president in the 2016 elections. These examples demonstrate that social media is not only the space where news is circulated, but where news is generated (Napoli, 2015, p. 2).

Governments around the world are also experimenting with technical means to invite public participation and interaction (Mickoleit, 2014). By adopting open data policies and expanding social media strategies, some governments are responding to the new communication and information era by imbuing citizens with more power over political interpretation and action.

However, strategies designed to effect positive information flows are being counterbalanced by attempts at controlling citizen-produced information flows. States are adapting more “traditional” methods of controlling media, such as censorship and surveillance, to this new ecosystem, affording states with the potential to monitor more individuals than ever before. Revelations made by Edward Snowden about of Middle Eastern governments in shutting down social media networks during the Arab Spring have shown that this wide and distributed decentralized network can be controlled by a powerful program, or switch.

Communication that was previously protected because of the inability of states to categorize and legislate new communication technologies is now being captured under old legal regimes. Slowly, states are adapting and extending the reach of older laws governing freedom of the media to the new communication era. In Hungary, a media law introduced in 2010 gave the center-right government the power to take punitive measures against media, including websites and personal blogs (Shnier, Slow and Steady: Hungary’s Media Clampdown, 2014). One panelist recounted how, in Turkey, a beauty queen was jailed for anti-government sentiments she expressed over the Instagram platform (Associated Press, 2015).

The majority of the panels addressed the ways powerful state and non-state actors are taking advantage of new sociotechnical realities. As traditional powers emerge onto a space that was, ostensibly, governed by the public, it is important to consider how the same affordances that have enabled the freer flow of information across time and space over the past few years are being strategically used by powerful state and non-state actors to advance their own aims.

For instance, social media is affording powerful state and non-state actors the potential to shape domestic and international communication strategies separately, through different means. According to one Milton Wolf panelist, Iran’s social media strategy, originally developed under Ahmadinejad, was crafted by “Western educated Iranians, under 35.” Their English-language social media strategy presents a softer side of Iran than seen before but, depending on the medium, not one Iran itself will see without the use of VPNs (Keating, 2013).

This bifurcated social media strategy can also be seen in the use of the echo chamber—the current media landscape in which information and narratives are reinforced or reinterpreted through repetition through blogs, tweets, and other media channels—as an advantage. An ISIS video depicting the beheading of an American journalist elicits two strong opposing reactions, but each prompts the same action. Whether a viewer is impressed or repelled, they will click “Share,” “Retweet” or “Reply,” doing their part to make both their own and ISIS’s message travel further than before. The editorial judgment whether to disseminate and how is left to individual users (Napoli, 2015, p. 5). Even when first passed through an editorial lens, such as through The New York Times, the responsibility for making the information more or less visible still lies with the follower, friend, or family member who encounters the content in their feed (Singer, 2014, p. 3).

The New Geopolitics of Technologies

The technological affordances of networked communication cannot be separated from the human actors that are involved in the production, dissemination or facilitation of information flows.

Research into the “politics of platforms” investigates the sociopolitical reality of the technology that governs our lives (Gillespie, 2010). As state and non-state actors increasingly rely on online content providers to both spread and absorb information, their relationships to those platforms will play an important role in the development of online media governance frameworks. Knowledge of the role that, for instance, U.S. online content providers have been playing in the surveillance of citizens at home and abroad underscores arguments against the “neutrality” of these technology companies (Napoli, 2015, p. 2). More recently, discussions in this space have turned to the role of the algorithm, and the individuals responsible for writing it, as another way stakeholders are intervening—either intentionally or unintentionally—in the filtering and hierarchizing of news and information online.

What responsibilities do social media companies themselves have in the current media governance landscape? Though we still think of companies like Facebook and Twitter as “technology companies,” they increasingly serve as the main source of news and information around the world. The gap that once separated social media platforms and news media has begun to narrow significantly (Napoli, 2015). Most recently, Facebook decided to experiment with inserting professional news publication stories directly onto their newsfeed—a program called “Instant Articles”—which signaled a major shift away from the old media model (Miller, 2015). Instead of leaving the site to go to The New York Times or NBC, readers will be able to read the articles these companies produce right from the Facebook app.

The lack of transparency of the algorithms that determine what news and information reach users should raise questions about the power of technology companies like Facebook and Twitter to make these decisions. For instance, last year it came to light that Facebook engineers, in collaboration with researchers from Cornell, were experimenting with the algorithm without users knowledge or consent. Known as the Facebook “emotional contagion” study, researchers were manipulating the news feeds of a half a million Facebook users in order to determine whether “positive” or “negative” posts influenced the extent to which others made positive and negative posts in response (Napoli, 2015, p. 6). This research, and its social and political consequences, suggests that, while these interventions are not illegal, the design of these algorithms is still a public concern, and oversight and regulatory mechanisms that have been deployed in similar contexts for media systems in the past are sorely needed (Napoli, 2015, p. 7).

Discussions at the 2015 Milton Wolf Seminar highlighted myriad ways state and non-state actors are adapting to the new communication era. As policymakers deliberate whether new technologies have changed or merely expanded the need for media regulation, it will be important to consider how the technological features of human-built technology both inhibit and enable certain actions. Like spectrum in the era of broadcast and space in the era of satellites, the underlying technological network and algorithms are becoming a collective concern. Discussions about global media governance should incorporate how social values, which have been built into governance frameworks in the past, are being built into the global communications and information policy of today.

Robyn Caplan is a SC&I Fellow and PhD student at Rutgers University’s School of Communication and Information and a Research Assistant for Data & Society. She also recently ended her tenure as a Research Fellow for the GovLab at NYU Poly. Her research focuses on information and data policy, open data, human information behavior, and social, economic and political issues emerging in the regulation of data. She earned her MA in Media, Culture, and Communication at Steinhardt’s School of Culture, Education, and Human Development, completing a thesis on jurisdictional issues emerging from remote data storage. She is the co-founder of AppAutopsy.com, an online application that uses data scraping and visualization to unveil politics and values in digital applications.

Robyn Caplan is a SC&I Fellow and PhD student at Rutgers University’s School of Communication and Information and a Research Assistant for Data & Society. She also recently ended her tenure as a Research Fellow for the GovLab at NYU Poly. Her research focuses on information and data policy, open data, human information behavior, and social, economic and political issues emerging in the regulation of data. She earned her MA in Media, Culture, and Communication at Steinhardt’s School of Culture, Education, and Human Development, completing a thesis on jurisdictional issues emerging from remote data storage. She is the co-founder of AppAutopsy.com, an online application that uses data scraping and visualization to unveil politics and values in digital applications.

Prior to accepting her fellowship at Rutgers, she worked as the Digital Editor for MAKERS.com, a PBS/AOL website on the history of the women’s movement in the United States. Robyn received her undergraduate degree from University of Toronto, and is originally from Ontario, Canada. She can be found on Twitter @RobynCaplan.

REFERENCES

Anadolu Agency. (2015, April 10). “OSCE Calls on Greek Cypriots to Reconsider Law on Armenian Killings.” Retrieved May 5, 2015, from Hurriyet Daily News

Associated Press. (2015, March 6). “In Turkey, Criticizing the President Can Land You in Jail.” Retrieved May 7, 2015, from The New York Times

Bossewitch, J., & Sinnreich, A. (2012). “The End of Forgetting: Strategic Agency Beyond the Panopticon.”New Media and Society, 0 (0), 1-19.

Gadi Wolfsfeld, E. S. (2013). “Social Media and the Arab Spring: Politics Comes First.” The International Journal of Press/Politics , 18 (2), 115-137.

Gillespie, T. (2010). “The Politics of ‘Platforms.’” New Media & Society , 12 (3).

Graham, M., Avery, E., & Park, S. (2015, March 11). “The Role of Social Media in Local Government Crisis Communication.” Public Relations Review .

Keating, J. (2013, September 5). “Iran’s Social Media Offensive.” Retrieved May 5, 2015, from Slate:

Lewis, S. C. (2012). The Tension between Professional Control and Open Participation: Journalism and its Boundaries. Information, Communication & Society.

McGee, M. (2014, February 28). Facebook Cuts Into Google’s Lead As Top Traffic Driver To Online News Sites [Report]. Retrieved from Marketing Land

Mickoleit, A. (2014). Social Media Use by Governments. OECD Working Papers on Public Governance, No. 26. OECD Publishing.

Miller, C. C. (2015, May 15). Why Facebook’s News Experiment Matters to Readers. Retrieved from The New York Times

Morgan, J. B. (2015). The ISIS Twitter Census. The Brookings Project on U.S. Relations with the Islamic World , 20.

Napoli, P. M. (2014). Social media and the public interest: Governance of news platforms in the realm of individual and algorithmic gatekeepers . Telecommunications Policy , 2.

Price, M. E. (2015). Free Expression, Globalism, and the New Strategic Communication. United States of America: Cambridge University Press.

Rea, P. (2013, January 3). Relying on Twitter During Hurricane #Sandy. Retrieved from The Huffington Post

Shnier, D. (2014, August 1). Slow and steady: Hungary’s media clampdown. Retrieved MY 7, 2015, from OpenSecurity: Conflict and Peacebuilding

Shnier, D. (2014, July 28). Slow and Steady: Hungary’s Media Clampdown. Retrieved from Canadian Journalists for Free Expression

Singer, J. B. (2014). User-Generated Visibility: Secondary gatekeeping in a shared media space. New Media & Society, 16 (1), 55-73.

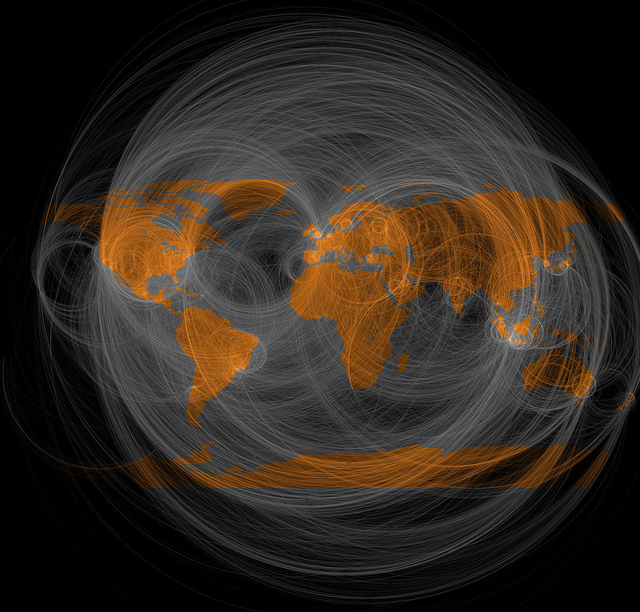

Photograph of the Geography of Twitter @replies by Eric Fisher via Flickr