From open borders to open data

This week, many of us have been gripped by the story of thousands of people, mostly from Syria, trying to travel from Hungary to Germany via Austria. The story reminded me of an earlier refugee crisis. I grew up in Austria, and remember the day in 1989 when Hungary opened its borders and East German citizens drove over in their flimsy-looking Trabants. Unable to get into West Germany directly, they went the long way round through the Czech Republic, Hungary and Austria. The initial trickle of refugees became a flood, and the Berlin Wall came down a few weeks later.

What a contrast to 2015. In 1989, the Cold War was ending, and opening the border was a big step towards a re-united Europe. Now, the governments are talking of re-establishing border controls, and the police with their Alsatians are once again patrolling the trains from Budapest. These are sad times if you believe in open borders, and deadly times if you are on the wrong side of a closed one.

Another contrast between now and 1989 is the dramatic increase in the quantity of data and information available to anyone with an internet connection. In the development community, we call this the data revolution. So in an attempt to see how the data revolution of 2015 compares with the political revolution of 1989, I set out to see what European countries are doing for people fleeing from the war in Syria, using their own data.

I started with the UK’s Department for International Development, which is one of the most open donors according to Publish What You Fund’s Aid Transparency Index. According to DFID’s ‘DevTracker’ website, the UK’s foreign aid budgeted for Syria in 2015/16 is GBP 152 million. That doesn’t count aid to Syrians in neighbouring countries like Lebanon or Jordan. Add those two and you get to GBP 256 million: about GBP 10 per Syrian citizen, per year. This does not include the cost of supporting Syrian refugees once they reach the UK, but these are likely to be negligible: so far, the UK has only admitted 4,200 Syrian refugees, approximately 0.1% of those who have been forced to flee the country.

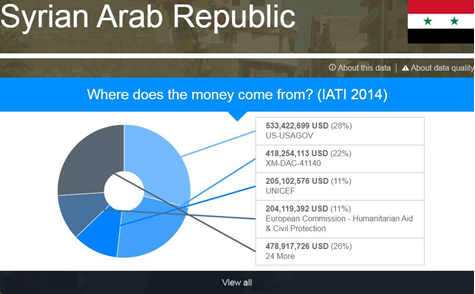

What about other donors? For this, I went to d-portal.org, which summarises all the data reported to the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI), the most up-to-date record of development flows. This shows total spending of USD 2 billion in 2014. The U.S. is the largest donor, providing just over a quarter of the total, with most of the rest coming from Europe and various UN agencies (though we’re not sure who ‘XM-DAC’ is).

There are other problems with the IATI data. One, it’s not always up to date. The U.S. contribution is shown as over USD 500 million for 2014 and zero for 2015, for instance. That’s clearly not true, and indeed the U.S. government’s own site, www.foreignassistance.gov records USD 365 m of spending on Syria in 2015 to date, of which 94% is humanitarian. It’s not clear why the U.S. government is capable of reporting to its own site but not to the IATI standard, which would make its data internationally comparable. Security is not a concern: most donors to Syria already redact the locations of projects and names of implementing agencies.

Two, not all countries are publishing to IATI. Germany’s Ministry of Development Cooperation (BMZ) publishes data on long-term development spending, for instance, but not humanitarian assistance, which is handled by its Foreign Office (Auswaertiges Amt). Austria and Italy do not publish any data, though both host refugees from Syria and elsewhere. The OECD’s Creditor Reporting System shows that Germany gave USD 316 m in in assistance to Syria in 2013; but that data is only made available two years after the event. That’s a good historical record, but no good for planning, or for activists trying to work out where their taxes are going.

Three, even where data is published the quality is often poor. The d-portal lists just one project by the Agence Francaise de Developpement (AfD) in the region: a support project for small businesses in the Tripoli and Bekaa regions of Lebanon. The project is recorded as starting and ending on the same day in 2010, with a single disbursement of EUR 196,000 paid in May 2015. It is not listed on the AfD’s own website, http://carte.afd.fr/afd/fr/pays/liban/. That site records 23 other projects in Lebanon on an interactive map with project descriptions, but none in Syria.

Missing and inconsistent data is more than an academic problem. The UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, OCHA, estimates that USD 7.4 billion is needed this year to meet all the humanitarian needs of people in Syria and its neighbouring states. We need to know how much has been contributed to this appeal – by the OCHA’s estimates only about one third is funded. The debate in Europe is also clouded by prejudice and ignorance, which populist politicians exploit to their advantage. Their voters need to know that over three-quarters of Syrian refugees are in Lebanon, Jordan or Turkey, not in Europe. They need to know that the UK is generous with its aid but not hosting refugees, Germany is generous with both, and Hungary with neither.

At Publish What You Fund, we believe that people have a right to information – whether it’s about what their government is doing with their money, or what others are doing for them. We don’t just want information for interest. We want it to fight corruption and waste. We want it to fight the ignorance and moral cowardice that characterise the collective European response to the refugees. And we want it so that citizens everywhere can have more power over their lives. If we can do that, then the data revolution could be as important as the political revolution of 1989.